This is the second and final part of my Mekong Delta story, continuing from the last post. Again, I apologize for the dearth of pictures.

The Vietnamese are very early risers. Things start buzzing between 5 and 6, and the market is usually the center of this activity in Vinh Long. A stroll along the narrow path between the stalls is a smorgasbord for the senses. Everything and anything one could imagine eating is here for sale, and in any state as well, from just born to freshly cooked. I see all kinds of fish, piled and stacked in tubs, some still flipping. Creatures lifted from the sea are present in all shapes and forms. There is a woman chasing down one of her frogs that has managed to escape from its bondage and hop away. I encounter a bunch of baby pigs in a metal crate poking their noses at me. Meat of all kinds is cut right here and hangs or is laid out on tables, the vendors shooing away flies. And then there are chickens. Chickens abound in every phase of life from the egg to the butchers blade. There are boxes and containers filled with yellow baby chicks, “boiled eggs “ (eggs with a little chicken in it that is eaten scooped out with a spoon), chickens tied up or in bamboo crates, and chickens being slaughtered, boiled and plucked. It all happens out in the open every morning. The sights, smells and sounds, though not for the timid, make for an entertaining and fascinating stroll. Fortunately, I am a vegetarian and I settle for fruit, biscuits and some noodles.

Pushing my luck I get back on the motorbike and head for Cantho, the unofficial capital of the Mekong delta. Along the way, something catches my eye. Telling myself it is better to stop and investigate than to pass and regret, I turn around and park the bike in front of a house. A dirt pathway leads to the front of the bamboo and wood house. A makeshift bamboo gate closes the path. Staring at me, through the gate, are two children. I throw out a polite “Hello” which results in giggles and smiles. This is exactly what I am looking for and I start taking pictures. I move a little closer and take a few more. Now the rest of the family has taken interest in this stranger. The father instructs the children to open the gate so the kids can pose proper for me, thus ruining the picture. They invite me to look around their house and once again two cultures share a brief moment with only “Hello” and “Thank you” as common language.

Once in Cantho I again head for the water and another boat ride. This time I take a Vietnamese row boat. These boats, usually operated by women, are rather small and can be seen all over the delta and throughout Vietnam. The paddler stands at the rear of the boat and uses her weight to push the boat forward. They may look small but these women are strong. No matter where I go it seems that women are always doing a greater share of the work. Anyway, it’s late in the afternoon and we head down the river as the sun begins to set. Along the banks of the river are many houses built up to and in many instances over the water on stilts. As the light fades, I can see into the houses as we pass in the water. The orange yellow glow of lights inside contrast with the blue dusk glow outside. In many houses the glow of a TV stands out sharply with the simple open bamboo and wood construction of the homes. Atop the homes the silhouettes of a jumble of TV antennas pierce the darkening sky. Even here the tube rules.

As we head back the woman rowing the boat shows me her house and asks if I would like to go to her house and meet her family. Once again confronted with gracious hospitality I accept. Inside the house, I am offered a cup of strong and pungent tea. I force myself to drink politely. The whole family is here – her children, husband, and others. The youngsters practice their few English phrases they know on me. I mimic what I hear in Vietnamese and everyone giggles. Soon an older woman and her daughter come into the house. She speaks hesitant English, “ What is your name? Where are you from?” I tell her I am American. She looks at her daughter. “She is American too, only we can’t find her father.” I look at her daughter and I understand; she is Amerasian, the daughter of an American soldier and this Vietnamese woman. The woman tells me they are trying to find the father in the U.S. so they could emigrate there. All she knows is that his name is Sam. “It was a long time ago, I don’t remember too much. I haven’t spoken English in a very long time,” she says. Her daughter, half American and half Vietnamese, is outcast and will have a hard time marrying in Vietnam. Though long gone, the aftermath of the war still lingers

On the road early in the morning, I have a long ride ahead of me from Cantho to Chau Doc near the Cambodian border. The road roughly follows the Hau Giang River, a major tributary of the Mekong. Everywhere I am surrounded by green, primarily rice fields. The rice fields are divided up into rectangular plots with walls of mud all around. These walls allow for the plot to be flooded with water before the rice is planted. By hand small rice seedlings are placed into the mud below the water. Rice fields can be seen at any stage of growth from a freshly flooded field to waist high sea of green ready to be harvested. Out in a large field I see some women working the fields, so I stop and have a closer look. To get out to where they are I have to negotiate the thin mud walls separating the plots. I find a woman who is amused by my curiosity in this everyday task. The purple shirt she is wearing makes for a wonderful contrast to the green surroundings. For a moment she gets a break to exchange hellos and to laugh at this curious looking fellow with a camera. And then she is back to work.

And I am back on the bike moving with confidence. A couple of days of riding have convinced me that I am invincible, swerving around pedestrians and women on bicycles, passing others on motorbikes with a confident wave and smile. Riding with the wind in my face I am king of the road…until a bus comes by out of nowhere with its horn blaring, nearly running me off the road. Humbled, I proceed with renewed caution. What if that bus hit me? Would I even get to a hospital? If so would the cure be worse than the affliction? I begin to realize how far away I am from the world that is so safe and familiar to me. And that’s the joy of it. Being so far away, in both distance and in culture.

And farther I went.

The midday air is hot. Fortunately the heat is tempered by the constant breeze from my motion. I realize exactly how hot it is as I stop for gas. Not being near a large town, I find that gas stations are few. Along the road in front of little food stalls or people’s homes are glass bottles filled with a clear yellow liquid. This is black market petrol. A few thousand dong (the Vietnamese currency where one dollar equals 11,000 dong) is exchanged, the gas is poured with a funnel and I am off. I ask no questions as to whose bright idea it was to store gasoline in a glass bottle.

Chau Doc was my favorite town in the Mekong Delta. Maybe because it was the farthest from Saigon. Or maybe it seemed to best fit my vision of what the Mekong delta was all about: river based communities pushed up to the water, small boats everywhere, houses on stilts jutting over the water, and floating houses built on the water with trap door openings to the fish farms underneath. It’s not that I didn’t see these things in other parts of Vietnam, but they all seemed to come together in the right proportion right here. Then again, maybe it was the wonderful an chay food stall right in the middle of the market. An chay is Vietnamese for vegetarian, and for about 75 cents I had splendid vegetarian meals of tofu and vegetables.

I hop on the public ferry and go across the river to Con Tien Island where I walk along a road lined with small wooden houses on stilts. A group of children follow me as I walk. I say “Sin chau” and they say “hello”, then I say “hello” and they say “sin chau” and everyone giggles. We repeat this giggly exchange as I wander about. Along the river side, a large family poses for me in the open part of their house as I point the camera. At the foot of the house in the river two pigs blissfully lounge in the muddy water. Further down I encounter men unloading barrels of petroleum from a boat. They roll the barrels precariously along a narrow plank of wood from boat to shore. Everywhere I go the mechanics of life play themselves out right in front of me – on the street or along the river, from the growing and processing of food and livestock, transportation of goods, to someone getting a haircut, a welder fixing a motorbike, a tailor making and mending clothing, people eating and sleeping, commerce and activity of all kinds out in the open. And I realize how shielded we are from most of these activities in the industrialized world.

Instead of taking the ferry back to town I allow a woman and her young son to take me back in a row boat. We slowly move past more houses high on stilts and a neighborhood of floating houses. The sun is low, and the light is magnificent on this side of the river. The dull gray wood of the houses has turned warm and golden. As we glide along the water, we pass other boats propelled by women in brightly colored loose fitting clothes, the long paddles gracefully raising above the water, with cargoes of produce, fish and a man with a bicycle. People pass by on the water with smiles directed at me, as the receding light adds a softness to the movement on the river. The Chau Doc side is already in shadow with a cool bluish light setting itself apart from the fading warmth across the river. For a moment, everything seems to be held together by the sheer quality of the late afternoon light.

Walking along the street that follows the river through town I see many narrow alleys paved of wood that jut out over the water connecting the houses along the water with the road. All this makes for a strange kind of neighborhood – rickety wooden pathways on stilts, no basements, just water. Boats and bicycles for vehicles. People are washing clothes or preparing and eating meals, kids are curiously following me around, desperately wanting me to point the camera at them. I really like this place. I like the simplicity, ingenuity, and functionality that it exudes. And of course the friendly welcoming smiles. Walking along one of the raised wooden sidewalks above the water I encounter a family eating dinner. The houses in this tropical climate are usually open to some degree. Privacy as we know it is virtually unknown here. They smile at my interest in them, sitting on the floor around large bowls of rice, fish and vegetables. They offer me some food, I gracefully decline and move on, chasing the remaining light.

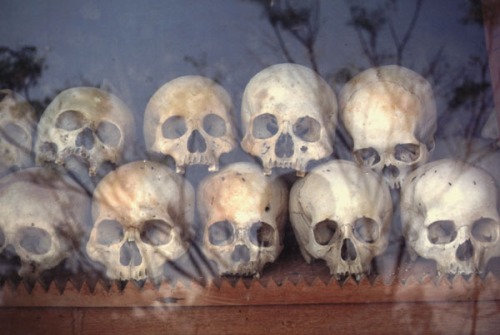

In the evening, I eat at a small restaurant where I am befriended by the family who runs it. Yet again, there is the ever present available daughter being highlighted for me. Before I know it an older uncle who speaks English has been summoned. We talk about his fine niece and I explain that although she is nice, beautiful and charming I am not looking for a wife in Vietnam. He translates as I speak and we all smile. I ask about the war and what has happened since. He is reluctant to elaborate his feelings. They were all very kind, and we ended up playing “lotto” (similar to bingo) all night. Everyone puts in 1000 dong and whoever wins gets the pot. I was embarrassed to have had good luck that night, to the disdain of one of the older aunts who seemed to think I was playing some American trick. I was hoping that the good luck would spill over into tomorrow, when I was to make my way further out to a place called Ba Chuc where the “bone pagoda” stands in haunting memory of the atrocities perpetrated by the Cambodian Khmer Rouge.

A long and uncertain road ahead of me, I make an early start on the motorbike, hoping that the chilling place I am going to is not an omen of my ultimate fate on this two wheeled death trap. Ba Chuc is where approximately 3000 innocent civilian Vietnamese were killed by the Khmer Rouge in 1978. The Khmer Rouge also slaughtered nearly one million of their own people during this time. I venture to this place to see for myself, to make the unreal very real.

The road takes me along channels of water leading out of Chau Doc used for flooding fields of rice and for fish farming with large nets that can be lowered and raised above the water. Just outside of Chau Doc is Sam Mountain, with its many temples and pagodas, standing out in the otherwise flat terrain. The road completely encircles the small mountain. Continuing on I leave the water, rivers and canals behind. The landscape seems drier here, but maybe it’s just the heat. The road stretches out in front of me and now I can see more mountainous terrain off in the distance towards Cambodia. The land begins to resemble the images of the “Killing Fields” I remember from the movie of the same name depicting what happened in this part of Asia during the 1970’s. It is decidedly less crowded here, barren for Vietnamese standards. In this vast open landscape I see two boys on a bike. The one in the rear is dressed in the bright orange robe of a Buddhist Monk, complete with shaved head. I chase them for pictures. We are equally amused by each other’s peculiarity.

At a small village the road to Ba Chuc veers off from the paved road and becomes a dirt and at times sand road pitted with craters. I feel an eerie sense of isolation and almost dread out here. People look at me with wonder as I maneuver the rough road on my motorbike. It must be rare to see a lone traveler out here. Feeling that I must be near the Bone Pagoda I ask along the way. They point down the road and let me know with their fingers that it is about 2 kilometers. I continue down the dusty road, 3, 4, 5 kilometers. I stop again wondering if I had passed it, but no, further down the road they point. “How far?” I ask. They indicate 2 kilometers. Skeptical, I wonder if it wasn’t a mistake to have come all the way out here. OK, I think to myself, 5 Ks no more. Fortunately at about 4 Ks I have found the dreaded place.

I park the bike and with trepidation and respect I approach a monument unlike any I have seen before. Staring at me through the glass walls of the six-sided structure are hundreds, if not thousands of skulls of the slaughtered innocent. Many of the skulls are broken by what must have been deadly blows. Behind the skulls are the other bones of the dead piled up in a gruesome mass. I feel like a voyeur looking at these poor souls stacked like a pile of rocks, almost undeserving of being here as I watch some Vietnamese come to silently ponder this part of their history. Inside the pagoda is a wall of photographs, thankfully in black and white, of many murdered people, men, woman, and even children, killed in horrible ways, bodies strewn on the steps and the grounds of the very pagoda I am standing in. In this solemn atmosphere a man eerily plays a flute in the other end of the room as the smell of incense fills the air.

Standing near the monument of skulls, I can overlook a wide field where a man with an ox driven cart moves alone. In the distance I look over to Cambodia and I realize I am at my furthest point. Far off and alone in many ways, my journey from here on is a process of returning. So back along the dusty road to Chau Doc I must go; maybe another night of lotto, to Vinh Long where Khanh and a cheerful dinner of an chay food wait for me, and then back to the rumble and roar of Saigon. And I realize not only will I travel in distance, along the rivers and canals of the Mekong, but in time as well, for I will travel from a war torn and agrarian past on towards the hectic and prosperous future that belongs to this land of the mighty river.